Amelia Earhart Memorial Flying Band

“The importance of RS is greater than it’s ever been. There has to be some way of addressing people who are so adversely affected by the wage gap, by poverty, by education systems that have not worked to their advantage for a long time ... Without RS, the people of 31st and Troost and the surrounding areas will be a lot worse off.”

You grew up on the East Side of Kansas City in the 1960’s. What were some highs and lows of your early life in the community?

Everybody knew everybody – kids and families were tight. We got together in the street for holidays. Families took care of each other’s kids. We played ball in the park, rode our bikes, and ran free. Our families were the working poor, blue collar people who worked hard. Everyone scraped to get by and worked hard to support their families and one another. There was a strong sense of community. There were some bad dudes, but not many. We knew who caused trouble and had guns and stayed away from them. There was no fear like there is over there today!

A low would be the riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. I was a junior in high school and driving home from a night-time job with three guys. Buildings were burning at 44th and Prospect. We turned the corner at Prospect and ran into the National Guard. The whole sky lit up. We were forced out of the car and onto the ground. That was very scary!

How did your experience in High School shape you?

I was an odd ball in our neighborhood because I went to Bishop Hogan Preparatory Academy. I was the only black student in a Catholic High School that served a predominantly white community. It was different growing up in a neighborhood that was all black and going to a high school that was all white. The experience shaped my thoughts about people and race. It shaped my thoughts about how we interact and treat one another. High school is where I started to become a mediator between two racial cultures. All of these things influenced my thoughts about what I was going to do. I knew I would become a lawyer.

It was interesting from a dating standpoint during the 60’s — who do you take to prom? The girl I really liked I couldn’t ask because she was white. So, do I take the girl from the neighborhood that I don’t really care for?

Eventually I dated a great girl! Her name was Ann and she went to school at Notre Dame de Sion, but we couldn’t be seen in public together. Her father was on the city council at the time. For my junior year prom, my best friend Chip Tate—rhythm guitarist in our band—wore my tuxedo and drove my parents' car to pick Ann up from her house on Ward Parkway. He brought her back to my place, I put my tuxedo on, and I drove Ann to prom. It was just the nature of the beast and what we had to do. Ironically, Notre Dame had their prom the same night and our band was playing the after-party. Ann couldn’t go in with me, so she sat in the car while I played.

You were the lead singer with Amelia Earhart Memorial Flying Band, an otherwise all white band in the late 60’s. Tell us something about the band’s context.

Most of the people in the band and the wider group we ran around with were affluent, with the exception of me and one or two others. The civil rights movement, the sexual revolution, and music were the cultural influences of the day. Being on both sides of the civil rights argument meant I was in very separate conversations about central issues. Talking about the Black Panthers with my family around the dinner table was a completely different conversation than the one I had at school the following day. It was a different conversation again than the one I had with the affluent people who hung out with our band. It was cool to be edgy and non-conformist in the 60's and I was certainly a non-conformist.

How did you handle the tensions as a teenager?

At school I didn’t know everybody but everybody knew me because of the color of my skin. I’ve always been outspoken and I’m not timid, so I ended up in leadership positions both in school and outside school. As a leader I was able to set my own agenda somewhat. That helped a lot. I made good grades and worked hard. I left home my senior year to live on my own and drew out the money I’d made to pay my school tuition – school was very important to me. I continued being in the band, that helped too.

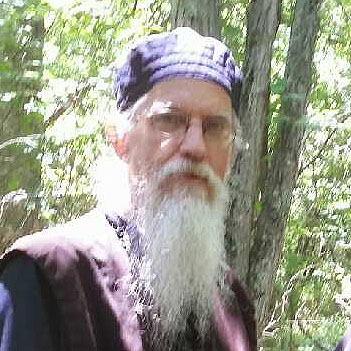

Photo by Tom Morse-Brown

My parents were traditional, relatively poor, black people and extremely suspicious of the white man. Later, they started making money for themselves and became Republicans. The kids in my school and their families were equally suspicious about the black community. They were just not sure they wanted black people in their neighborhood.

I didn’t really have as much suspicion of white people, neither did I have an immediate acceptance of what black people said about white people. I was accused by my neighborhood of not being black enough and on the other side in the white community, I was way too black. This tension still persists today.

Who have been your key mentors in life?

Two major people greatly shaped me and meant a great deal to me. The first was my Father. He was a mentor in a very silent and powerful way. Just watching him struggling in life and eventually succeeding, watching him maintain a strong sense of self and his own identity when he succeeded was very powerful. He was a direct and simple man with a lot of character and dignity.

The other key mentor was the senior partner—Bill Sanders Senior—in the law firm I joined when I first started practicing law. He taught me how to be a professional within the profession that I had chosen. A handshake from him was very important to me. He had a very keen mind and he was somewhat experimental. I remember he took me to trial with him and he turned to me (as we were picking the jury) and said, “You do it”. I’d never done this before, but he let me go on up and bumble and stumble around. He had arranged it with the judge ahead of time. He was a great mentor. When I told him I was leaving the firm, he cried.

Fr. Justin Mathews, Executive Director of Reconciliation Services, suggests that Troost isn’t just a dividing line in our city, it’s a dividing line in our hearts. Would you talk about your vision for the future of Troost?

It matters where you live, what it looks like, and how it feels. Physical changes and development are badly needed for the area. There’s need for infrastructure to attract further development in order to stimulate economic activity and jobs. But at the end of the day the whole concept of Troost, in my opinion, is much more psychological than physical. The psychological has driven the physical. I have hope that the physical development will help drive the psychological. The question is, who is going to be the developer of the psychology of the heart and soul of this area?

This is what you guys at Reconciliation Services are doing. You meet people where they are, as they come to you, in a way that lifts them up, regardless of what side of Troost Avenue they live on. I’m much aware of your trauma focused approach as you interact with people at RS. Trauma doesn’t always mean that you’ve been shot or beaten. Trauma can be atmospheric. You feel it and you’re affected by it! There are very few places in the Troost area where you’ll find an atmosphere permeated with reconciliation and peace.

The importance of RS is greater than it’s ever been. There has to be some way of addressing people who are so adversely affected by the wage gap, by poverty, by education systems that have not worked to their advantage for a long time. There has been dis-investment, lack of opportunity and, therefore, there is lack of hope. Without RS, the people of 31st and Troost and the surrounding areas will be a lot worse off. If RS can do more than what they currently do the neighborhood will be a lot better off and so will our city at large.

What would be the one thing you’ve learned from your personal life experience that you would like to share with others?

I learned in the Marine Corps that I could pretty much accomplish anything in life that I wanted if I just kept with it. The Marine Corps taught me to be mentally tough. There were many times I wanted to crawl in a hole and quit, but I didn’t. I learned that no matter how bad things look today, if I show up tomorrow they won’t be as bad. I’ve learned to look at what I do have as opposed to what I don’t have. I think that keeps me happier.

A core value of RS is to reveal the strengths of the people around us. How have you tried to see strength and possibility in others?

I try very hard not to accept the visual first impression as being true, in most instances. I believe every individual person has something of value that they can leave you with. I’ve been blessed with the breadth of people I’ve come across in my life in so many different places. When I left home at 16, I was homeless. I remember sleeping on the steps of the Art Gallery in the summer time. There was a bunch of us runaways there who needed a place to crash. Some guy—who initially looked really weird—offered me something to eat. After spending time listening to him I realized that he was very different than what I first thought.

If you spend time with people ... if we will listen and empathize a little bit, a connection can happen. If we give people a chance they are likely to surprise us. I like to think I surprise people!

This blog is excerpted from an extensive interview on 9-9-16 by Father Justin Mathews, RS Executive Director, and Lyn Morse-Brown of Morse-Brown Creative. Written by Lyn Morse-Brown.